I just finished reading a nifty YA novel! There was a lot to like, but I had a few minor issues with the writing. On the plus side, reading a novel with problems lets you see the mechanics of story better, sometimes, than a reading a novel where it all comes together wonderfully. When everything in a story works, you don’t see the parts, just the glorious whole. But when there’s a glitch somewhere, you can often see what went wrong, and that tells you something about what to do and not do in your own writing.

In this particular instance, I noticed an issue I’ve often seen before: the author seems to forget things that have happened to the protagonist and should be continuing to affect him. Physical things, like injuries or being wet or dirty. The first-person protagonist of this novel gets hurt a lot, and unless his injuries have plot significance, they seem to fade very quickly from his awareness. Not only that, other characters don’t comment on them. It’s as if they never happened.

Here are a few things the protagonist does during one particularly eventful day in the book, when most of the climactic action takes place. In order of occurrence, he:

- gets thrown against walls by super-strong evil robots (several times)

- throws up

- burns his hand on hot machinery

- is hurled across a twenty-foot-wide chasm onto a rock ledge, where he lands “chin first” and scrapes up the whole front of his body

- hikes through the woods in the rain

- gets swept down a frigidly cold river

- slips in blood and gets it on himself

- runs, runs, runs from the scary robots

- gets tied up so tightly he can hardly breathe and hung upside-down over a burning room

There’s probably more I’m forgetting. Oh, also, by the end of all this, it’s evening, and he hasn’t eaten or drunk anything all day.

The author does a good job remembering that our hero is wet after his dip in the river, and the burned hand comes up later when he’s thinking of his love interest, who he was helping when he got burned. Other than that, though, he doesn’t act like a guy who’s been battered and shredded and exhausted. Nor do other characters look at him and go “DID YOU GET RUN OVER BY A LAWNMOWER OMG.”

Young, healthy people, like our sixteen-year-old protagonist, heal pretty quickly, but this is all in one day. And yes, for most of that day, he’d be running on adrenaline and maybe not noticing his pain, injuries, bloodied appearance, etc. But he’d notice it later, and other people would notice it when they looked at him. When a writer isn’t consistent on this stuff, it’s hard to stay immersed in the protagonist’s point of view. It creates an empathy gap.

But take heart! I bring you an editing tool to help make sure that when your characters get hurt, they stay hurt! (Or wet, or dirty, or paint-spattered, or whatever.) Right up until they logically shouldn’t be hurt anymore!

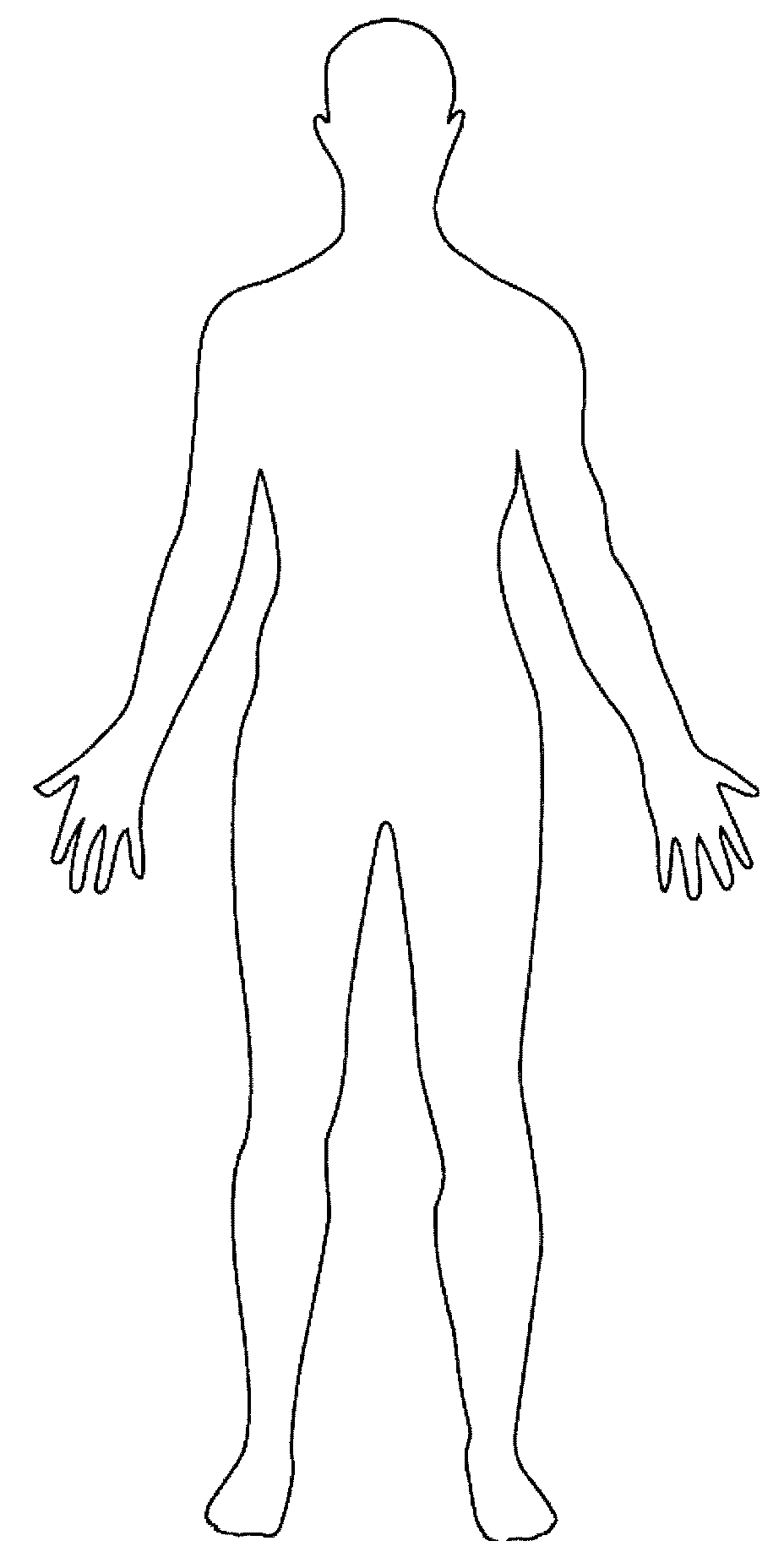

This image is available for free download here, along with some other templates of the human body. I recommend you just take it off of this post, though, as I cleaned up the lines a bit from the original.

Got a character who’s about to have a rough day? Why not print one of these handy outlines and draw on it to give yourself a visual reminder of what’s happened to her? (The body shape won’t match every character, of course – even without accounting for those who aren’t human – but it’s a start.) You can use it to keep track of the character’s appearance (“You’re covered in mud!”). You can also make note of injuries that might not be visible, but should still affect the character. For instance, if she’s wrenched her shoulder badly, you might shade it in red to remind you that she’s going to keep feeling that awhile, especially if she tries to climb or throw something with that arm.

Have you run into this in your reading (or your writing)?